Thousands of migrant children, also known as “unaccompanied minors,” have crossed into the U.S. across the border from Mexico. The majority are from Central America, where young people have been forced to leave due to continued poverty, civil war, and gang violence. Most of these children come from Central America. Many are crossing along the Texas border, and typically tell stories of leaving to unite with one or both parents, undocumented, in the U.S., and/or to flee for safety from the dramatic rise in violence and extreme poverty in Central America. The children have described how they have become targets of drug cartels, and have been subject to threats or acts of violence.

In 2021 under the Biden administration, many unaccompanied children seeking asylum have been returned under the Title 42 code that was enacted under the Trump administration as a mechanism to refuse asylum seekers and migrants seeking to enter the U.S. at the southern border, under the guise of a public health decree during the pandemic. Those that have been permitted to enter have been held in detention facilities for minors for lengthy periods rather than being released to family members waiting in the U.S.

We are calling on the Biden administration to:

- Protect the rights and wellbeing of children, including the right to seek asylum

- Rescind Title 42 health code that is being used to expel children and asylum seekers at the border

- End the use of influx facilities for unaccompanied migrant children and invest resources in ensuring children are released to their families as soon as possible.

- Provide small scale, homelike settings with trained case workers for children in cases where short-term housing is necessary.

Children, just like adults, have the universal human right to seek and enjoy asylum from harm. Unaccompanied migrant children are often targeted precisely because they are children, and are even more vulnerable to human rights violations than adults. Compounding the potential harm they face in each country and every step along the migrant trail, they are then often routinely denied access to asylum and other protection systems.

From 2018 to 2021, the governments of both Mexico and the USA have forcibly returned unaccompanied migrant children to their countries of origin, without adequate screenings for potential irreparable harm they could face there. Yet even prior to then, unaccompanied migrant children had uneven access to asylum procedures both within Mexico and at the US–Mexico border, which persists today.

Since January 2021, under the new administration of US President Joseph Biden, tens of thousands of unaccompanied migrant children from Central America and Mexico have crossed irregularly into the USA along the US–Mexico border. The majority of those children are seeking safe haven from targeted violence and other human rights crises in their countries of origin. One in every three migrants and asylum-seekers from Central America and Mexico is a child, and half of them are unaccompanied by family members or other adults. In more than 80 percent of their cases, these children are hoping to reunify with family members who are already residing in the USA, according to the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

After these unaccompanied children have fled life-threatening insecurity in their home countries, they have then faced new threats of systematic pushbacks and forced returns by US and Mexican authorities to those very countries where many escaped death threats or other irreparable harm. Under national and international law, both the US and Mexican governments are legally obligated to determine and act in the children’s best interests when receiving them. Instead, they are often failing to conduct adequate screenings of potential harm that the children could face upon return to their countries of origin, and are in some cases forcing them back into harm’s way.

Excerpt from Amnesty International’s report Pushed into Harm’s Way: Forced Returns of Accompanied Migrant Children to Danger by the US and Mexico (June 2021)

Child Detention FAQ from Detention Watch Network provides some context (April 29, 2021) for what is happening to unaccompanied minors :

Across the country different types of facilities are opening for unaccompanied children arriving at the border. In some instances, local governments are coordinating with federal agencies to use stadiums and convention centers to hold children. In other instances, the administration is using military camps and bases. There are two types of facilities we are currently seeing an expansion of: “influx facilities” and “emergency intake sites.

The U.S. has treated such children from Central America differently than those of Mexican origins — even though they may share the same experience. Those coming from Central America have been given an opportunity to apply for asylum, may be placed under the protection of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, and efforts made to reunite them with family in the U.S. Mexican children have been summarily deported back to Mexico.

These children in crisis need to be treated as refugees and should be provided humanitarian assistance. They should not be locked up in detention centers or deported. Moreover, steps should be taken to begin to address the root causes beneath this crisis — the driving factors of poverty and violence in Central America. U.S. failure to provide adequate visas for legal immigration, as well as, the lack of opportunities for legalization of undocumented and family reunification — also factor into the present crisis.

UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN OVER PAST YEARS

The ebb and flow of children in migration has been happening throughout the past decades, with push factors including turmoil and violence in home countries, gang threats, extreme poverty exacerbated by the impacts of climate change. Here are a few reference materials related to Unaccompanied Children over past years:

In January 2017, the Congressional Research Service published a report on unaccompanied children, which notes that in the first two months of FY2017, over 14,000 unaccompanied minors were apprehended by Border Patrol.

Unaccompanied Migrant Children in the United States: Research Roundup. Alexandra Raphel, Journalist’s Resource. July 15, 2014. This provides useful background information and definitions. It also has a great amount of links and resources.

THE NORTHERN TRIANGLE: CONTEXT FOR FORCED MIGRATION

The National Alliance of Latin American and Caribbean Communities (NALACC) mobilized delegations in September 2014 to visit El Salvador, Gutatemala and Honduras on a fact-finding mission concerning Central American migrant children. Read their Preliminary Findings and Recommendations. Visit their website at www.nalacc.org for more background and information.

The AFL-CIO led a labor delegation to Honduras in October 2014, meeting with workers, faith, labor, community partners and government officials. Their report, “Trade, Violence and Migration: The Broken Promises to Honduran Workers,” elaborates on the impact of US trade and immigration policies and provides an excellent backdrop and context for the general phenomena of migration out of Honduras, and in particular, the rise of the migration of children and their families.

Why Central American Children are Fleeing their Homes American Immigration Council (July 2014)

The Children of the Drug War: A Refugee Crisis, Not an Immigration Crisis. New York Times in-depth report on the children refugee crisis, by Sonia Nazario. July 11, 2014.

Debunking 8 Myths About Why Central American Children Are Migrating. In These Times, by David Bacon. July 8, 2014. Narrates how U.S. policy has fueled violence and instability in the regions where these children are escaping from.

APPREHENSION AND DETENTION

The Refugee Jail Deep in the Heart of Texas: A consequence of the restrictions imposed on Central American children and their families who have been crossing the border to flee from widespread violence and poverty has been the incarceration of families. This narrative, with photos, describes the situation at the family detention center in Killey, Texas.

Policy Recommendations on Unaccompanied Minors and Women at the US-Mexico Border. Authored by the South Texas Human Rights Center and the Working Group to Prevent Migrant Deaths, Aug. 5, 2014.

Kids First: A Response to the Southern Border Humanitarian Crisis. U.S. Congressional Progressive Caucus proposal. July 9, 2014. Placing “kids first” and labeling the influx as a refugee crisis, this proposal offers a multifaceted solutions. Its Root Causes section is particularly commonly overlooked in mainstream discussions.

NNIRR Urges President Obama to Act for Human Rights and Justice. NNIRR’s Commentary on the current crisis. July 1, 2014.

President Obama’s Announcement of Executive Action to Address Migrant Children Border Crisis. June 30, 2014.

Mexico’s Other Border: Security, Migration, and the Humanitarian Crisis at the line with Central America. By Adam Isacson, Senior Associate for Regional Security; Maureen Meyer, Senior Associate for Mexico and Migration; and Gabriela Morales, Consultant. June 17, 2014

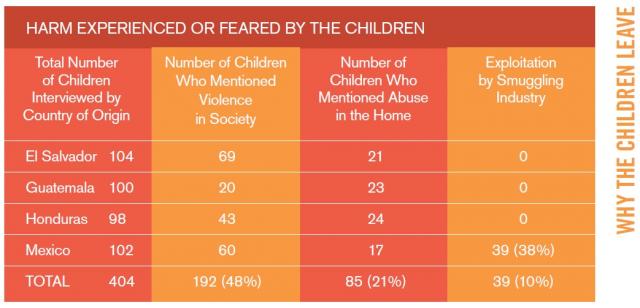

UNHCR Report: Children on The Run: Unaccompanied Children Leaving C. America and Mexico & the Need for International Protection Children on The Run: Unaccompanied Children Leaving Central America and Mexico and the Need for International Protection. (Executive Summary) Published by UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, March 2014. UNHCR analyzes the humanitarian impact this insecurity has had on children, forcing them across international borders to seek safety on their own. The agency calls on Governments to take action to keep children safe from human rights abuses, violence and crime, and to ensure their access to asylum and other forms of international protection.

What New Border Patrol Statistics Reveal about Changing Migration to the United States. Migrants, increasingly non-Mexican, are arriving in Texas — and frequently dying in remote areas. By Adam Isacson, Washington Office on Latin America. Jan. 30, 2014.